Wikis in a Pandemic

The code behind the Wikipedia article on the history of wikis

The first wiki was created in 1995 by Oregon programmer Ward Cunningham who named it after the "Wiki-Wiki" (meaning "quick") shuttle buses at the Honolulu Airport. They were meant to be web sites on which anyone could post material without knowing programming languages or HTML.

The most famous wiki is still Wikipedia which officially began with its first edit in January 2001, two days after the domain was registered by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger. This fact comes from, of course, an article on Wikipedia about the history of Wikipedia.

Wikipedia didn't get huge numbers of visitors immediately and it certainly didn't gain acceptance in academia for at least a decade. (Some might argue that it still isn't accepted by faculty for student use, especially when it is used in a copy/paste manner - but that's a different topic.)

I've been writing about wikis on and off since this blog started and a search on here shows 100+ mentions of "wiki" with about a third of those being actual posts about wikis. Most of that writing was in the first 15 years of this century, but I have seen some reemergence in wiki use among educators lately.

Back in 2005, I started getting into using wikis. Tim Kellers and I made one in order to teach about the use of wikis - particularly the use of open-source wiki software. It was what some would call a metawiki - a wiki about wikis.

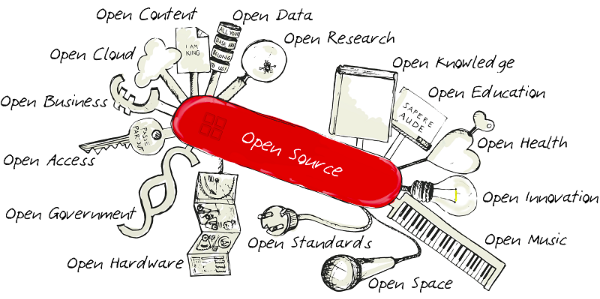

Wikis were part of the Web 2.0 movement. when we started to think about the Internet as a place where we could build and contribute our own content rather than just read and consume.

In 2005, we were mixing wikis in with the somewhat sexier 2.0 tools like podcasting, blogging, and the photo and video sharing sites that were popping up. Then came social media and everything changed again.

That metawiki that Tim and I made 15 years ago no longer exists since neither of us is still at NJIT where it was hosted. It served its purpose which was to demonstrate to others how wikis are built, grow, get damaged and heal. It looked a lot like Wikipedia because we used the same software - Mediawiki - that was used to build Wikipedia. [Note: The wonderful archive.org did crawl our pages and you can see an archived version of our Wiki35 there.]

Brother Tim and I were doing workshops on blogs, podcasts and wikis which were three things we were sure were going to change corporations and education. Blogs and podcasts are still powerful and still growing. Wikis? Not so much.

People often described wikis as "collaborative web sites" and they were being used for things like project management, knowledge sharing and proposal writing. The benefits of this collaborative approach include reducing daily phone calls, e-mails and meeting time as well as encouraging collaboration. The Internet research firm, the Gartner Group, predicted in 2006 that Wikis would become mainstream collaboration tools in at least 50% of companies by 2009.

Midway between that prediction, I wrote in 2007 that by my calculation technology generally moves into the world of education in dog years because it seems to take about 7 years for widespread acceptance and usage. This is in comparison to the world outside education, especially if the business world.

It's not that you can (or should) use the application of new technologies in the commercial world as a gauge for what we should be doing in education, but schools certainly lag behind industry and home users in adopting and adapting technology.

By 2015, I was writing more about the disappearance of wikis and the devolution of Web 2.0. My own use of wikis as tools in my teaching was also winding down.

I had been using Wikispaces with students as a collaborative tool. I assigned students to work in a class wiki and also had students create their own wikis using that software. But Wikispaces started to shut down and was gone by 2018. Now you can only read about it on Wikipedia.

It has been five years since that post and I don't think I have written anything significant in the interim about wikis. Some people are still using wikis and Wikipedia is in the top ten most visited websites on the Web, but I don't see people building wikis for education (and perhaps not in corporations either).

Blogs like WordPress and DIY website services overtook wikis as free or low-cost ways to put content online in pretty packages, though few of those are collaborative in the sense of wiki collaboration.

I no longer work on any wikis other than editing Wikipedia and I don't think Tim does either. But just recently, amidst all the scrambling to get courses online due to the COVID-19 virus pandemic, I saw a few examples of wikis in education that make me think that we haven't completely hit the DELETE key on wikis.

One example is at coursehero.com with a Comparative Anatomy and Physiology course in which Dr. Glené Mynhardt has students create a wiki page on one specific animal phylum. In an article about the course, Explore More in a Survey Course with a Build-a-Wiki Project, Mynhardt explains how she uses Moodle which allows for page creation using easy cut-and-paste and drag-and-drop commands.

One missing wiki element in Moodle is that it does not allow public access which is key to the original intent of wikis. Mynhardt says “Students can view each other’s wikis, but I can’t share them with colleagues or [the public], and the students can’t share them outside the course,” so educators who want to make the work public may want to use other web page–building options. It's not Mediawiki but using these wiki tools that are in a learning management system like Blackboard or that tool in Moodle or in collaborative software such as Sharepoint or simply creating a content page in Canvas and allowing students to edit the page is a way to bring the collaborative wiki experience to students. And in this time of students sheltering at home and working online more than ever, collaboration is an important element of learning.