The Science of Learning

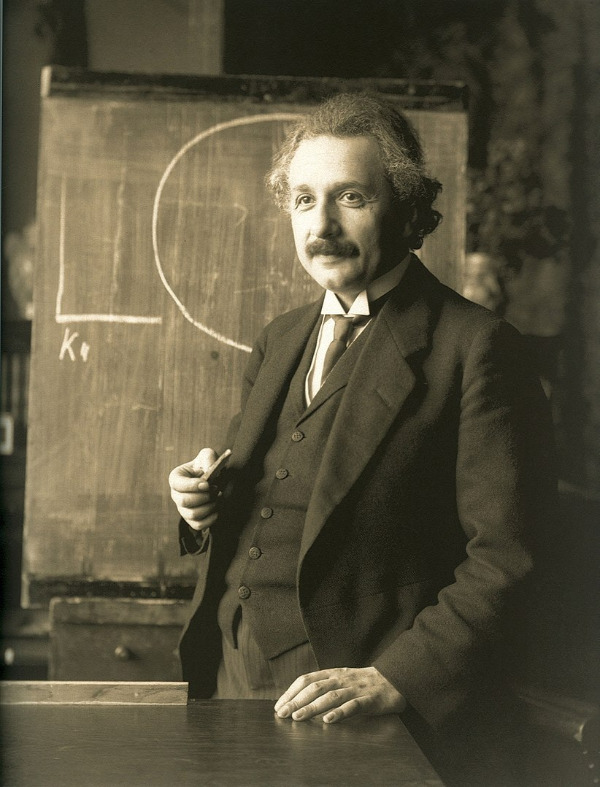

Albert Einstein was definitely a subject matter expert, but he is not regarded as a good professor. Einstein first taught at the University of Bern but did not attract students, and when he pursued a position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, the president raised concerns about his lackluster teaching skills. Biographer Walter Isaacson summarized, “Einstein was never an inspired teacher, and his lectures tended to be regarded as disorganized.” It's a bit unfair to say that "Einstein Was Not Qualified To Teach High-School Physics" - though by today's standards he would not be considered qualified. It probably is fair to say that "Although it’s often said that those who can’t do teach, the reality is that the best doers are often the worst teachers."

Beth McMurtrie wrote a piece in The Chronicle called "What Would Bring the Science of Learning Into the Classroom?" and her overall question was: Why doesn't the scholarship on teaching have as much impact as it could have in higher education classroom practices?

It is not the first article to show and question why higher education appears not to value teaching as much as it could or should. Is it that quality instruction isn't valued as much in higher education as it is in the lower grades? Other articles show that colleges and most faculty believe the quality of instruction is a reason why students select a school.

Having moved from several decades in K-12 teaching to higher education, I noticed a number of things related to this topic. First of all, K-12 teachers were likely to have had at least a minor as undergraduates in education and would have taken courses in pedagogy. For licensing in all states, there are requirements to do "practice" or "student teaching" with monitoring and guidance from education professors and cooperating teachers in the schools.

When I moved from K-12 to higher education at NJIT in 2001, I was told that one reason I was hired to head the instructional technology department was that I had a background in pedagogy and had been running professional development workshops for teachers. It was seen as a gap in the university's offerings. The Chronicle article also points to "professional development focused on becoming a better teacher, from graduate school onward, is rarely built into the job."

As I developed a series of workshops for faculty on using technology, I also developed workshops on better teaching methods. I remember being surprised (but shouldn't have been) that professors had never heard of things like Bloom's taxonomy, alternative assessment, and most of the learning science that had been common for the past 30 years.

K-12 teachers generally have required professional development. In higher education, professional development is generally voluntary. I quickly discovered that enticements were necessary to bring in many faculty. We offered free software, hardware, prize drawings and, of course, breakfasts, lunches and lots of coffee. Professional development in higher ed is not likely to count for much when it comes to promotion and tenure track. Research and grants far outweigh teaching, particularly at a science university like NJIT.

But we did eventually fill our workshops. We had a lot of repeat customers. There was no way we could handle the approximately 600 full-time faculty and the almost 300 adjunct instructors, so we tried to bring in "champions" from different colleges and departments who might later get colleagues to attend.

I recall more than one professor who told me that they basically "try to do the thing my best professors did and avoid doing what the bad ones did." It was rare to meet faculty outside of an education department who did any research on teaching. We did find some. We brought in faculty from other schools who were researching things like methods in engineering education. I spent a lot of time creating online courses and improving online instruction since NJIT was an early leader in that area and had been doing "distance education" pre-Internet.

Discipline-based pedagogy was definitely an issue we explored, even offering specialized workshops for departments and programs. Teaching the humanities and teaching the humanities in a STEM-focused university is different. Teaching chemistry online is not the same as teaching a management course online.

Some of the best parts of the workshops were the conversations amongst the heterogeneous faculty groups. We created less formal sessions with names that gathered professors around a topic like grading, plagiarism and academic integrity, applying for grants, writing in the disciplines, and even topics like admissions and recruiting. These were sessions where I and my department often stepped back and instead offered resources to go further after the session ended.

It is not that K-12 educators have mastered teaching, but they are better prepared for the classroom from the perspective of discipline, psychology, pedagogy, and the numbers of students and hours they spend in face-to-face teaching. College faculty are reasonably expected to be subject matter experts and at a higher level of expertise than K-12 teachers who are expected to be excellent teachers. This doesn't mean that K-12 teachers aren't subject matter experts or that professors can't be excellent teachers. But the preparations for teaching in higher and the recognition for teaching excellence aren't balanced in the two worlds.

Trackbacks

Trackback specific URI for this entryThe author does not allow comments to this entry

Comments

No comments