Do We Really Need To Make A Case For Teaching Literature?

Do we really need to make a case that teaching literature in the 21st century is worthwhile? A colleague gave me a copy of an article titled "The Case for Literature" by Nancie Atwell from Education Week that says we do.

I first encountered Atwell in 1989 after her book In the Middle: New Understandings About Writing, Reading, and Learning

In the article, Atwell begins:

A few weeks ago, I received an urgent e-mail: The National Council of Teachers of English is looking for volunteers for an ad hoc task force whose charge is to gather evidence about why literature should continue to be taught in the 21st century. Apparently, the worth of book reading had become an issue among the work groups that, behind closed doors, were writing the K-12 “common-core standards” that promise to shape curriculum in U.S. classrooms. Given that the Common Core State Standards Initiative is dominated by test-makers and politicians—representatives from the College Board, ACT, Achieve, the Council of Chief State School Officers, and the National Governors Association—I was dismayed, but not surprised, that the NCTE was finding it necessary to lobby on behalf of literature.What I remember from the book (which I have not looked at in at least ten years - I passed on my copy to the next generation when I "retired" up to higher ed) mostly was concerned with writing. Serendipitously, I was working yesterday on a student workshop that I doing this week on "The Reading/Writing Connection" so the article and my recollections about Atwell's book were all clicking together well.

My imperfect mental notes that I took away from her book would include these:

My imperfect mental notes that I took away from her book would include these:Conference with students about their writing and reading.

Use more mini-lessons and think of them as "whole group" writing conferences.

Teachers as writers. Model good writing. Not things you write in class. Go home and do homework and bring it in like you ask them to do - and share things that don't work too.

Teach more contemporary and young adult literature and less of the canon. (more on that later)

Test out your rubrics with your own writing. Teachers often assign things that are far more difficult than they imagine because they never actually attempt the assignments on their own. It's a lot easier to say "write a sonnet" than it is to write a sonnet.

Writing workshops. The class IS a writing workshop.

Kids like memoir and poetry if it is used as a way to talk about their lives.

Nancie Atwell

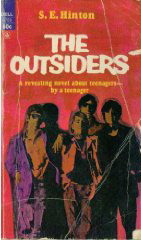

She is critical of the "canon-obsessed camp of Diane Ravitch and E.D. Hirsch Jr." who she feels are "either unaware or dismissive of the glories of contemporary literature." I taught a lot of young adult literature and I never have seen students at any level so into their reading as my middle school students. One of my former students (now also working in higher ed) told me recently that her daughter (who attends the same school where I taught her mom) was reading S.E. Hinton

She is critical of the "canon-obsessed camp of Diane Ravitch and E.D. Hirsch Jr." who she feels are "either unaware or dismissive of the glories of contemporary literature." I taught a lot of young adult literature and I never have seen students at any level so into their reading as my middle school students. One of my former students (now also working in higher ed) told me recently that her daughter (who attends the same school where I taught her mom) was reading S.E. HintonWhen I started teaching that book, it was already ten years old, but it held its grip on my middle school students for all the years I taught it. I knew the book over, under, sideways, down. My original paperback copy has almost as much marginalia as printed text. My students didn't want the book to end, and they wanted to read anything else she wrote, so my class library (another Atwellism) had lots of Hinton paperbacks. When the film version came out in spring 1983, my students that year (I timed assigning the book to precede and conclude just before the release) already had a very detailed film in their mind. I met many of them "unofficially" at the local movie theater the Saturday night it opened. Today I might be officially reprimanded for doing that. After the film was over and the tears were dried, we felt like we should have had a rumble outside - but instead we walked across Route 10 and got ice cream at Friendly's, and critiqued the film. No one could top the book version for my students, but Francis Ford Coppola had come pretty close.

Atwell says that she can "draw a straight line from particular authors of excellent young-adult fiction to particular authors of excellent fiction for adults" and I see that line very clearly too. Copper Sun by Sharon Draper to Toni Morrison. Gary Paulsen's Hatchet to Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild. Readers of YA novels by Nick Hornby and Michael Chabon are very likely to take on their adult novels at some point too - perhaps years later.

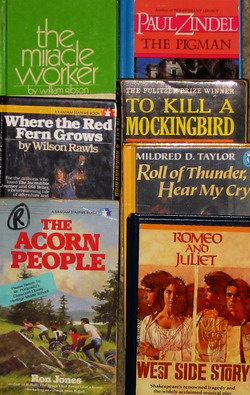

Atwell says that she can "draw a straight line from particular authors of excellent young-adult fiction to particular authors of excellent fiction for adults" and I see that line very clearly too. Copper Sun by Sharon Draper to Toni Morrison. Gary Paulsen's Hatchet to Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild. Readers of YA novels by Nick Hornby and Michael Chabon are very likely to take on their adult novels at some point too - perhaps years later.I didn't teach only young adult fiction. One of my most successful literature units in grade 7 was one that paired The Outsiders with our reading of Romeo and Juliet and the Shakespeare research project. One year I recall that in my end-of-the-year poll, Shakespeare beat out Hinton for the top spot.

And I can stilll recall some of the very heated discussions at the end of the year when I asked them to create and defend table seating arrangements for a party (they chose: wedding, sweet 16, bar mitzvah etc.) where all the characters from our reading were attending. Would you seat the greasers with the Capulets or the Montagues? Would Pony hit it off with Juliet? Could you imagine the problems if John from Paul Zindel's The Pigman

The National Endowment for the Arts has reported that only 30 percent of students in middle school read every day. I'm not a big defender of standardized tests, but when I read that, according to the NAEP, 70 percent of U.S. 8th graders in 2007 read below the "proficient" level I don't understand it. What happened since I was in that classroom? They don't read well because they don't read enough.

I taught a college reading class last fall and I saw it there too. They don't read outside of class for pleasure, and too many of them don't read for school either. We are losing them.

It seems that the Common Core State Standards Initiative is fine with pushing writing in the classroom, but without the reading and literature connection, I think the writing will fail. It's like coaching the defense but not the offense, or teaching them to draw or paint or play a musical instrument but not looking at paintings and drawings or listening to other musicians.

Trackbacks

Trackback specific URI for this entryThe author does not allow comments to this entry

Comments

No comments