In 2011, I made presentations at several colleges about the use of mobile apps in education and teaching in an "app world." At that time, apps were a big topic in the tech world but not a big topic in education. That presentation (it is on my Slideshare site) included the slide below where education doesn't even appear as a category unless you consider it to be part of the 5% of "other" app consumption. Clearly, games and social networking dominated usage at that time and they both still garner a high percentage of app use.

Showing this slide to college faculty reinforced their idea that apps are not for education. Of course, in 2011 apps were also not for common banking and financial use, medical records, and other "serious" computing.

That has certainly changed. But has it changed for education?

Reviewing my own 2011 presentation predictions, I said that I thought apps would come to education in three waves: Adoption, Adaption, and Creation.

Adoption was schools and educators adopting existing apps that had some education features or were designed for education. The obvious one then and now was apps for learning management systems. Blackboard was the first I used but now Canvas and all the other players have them. Adoption was not immediate. The two colleges I worked at then both chose not to offer the mobile version. Faculty could not see how you could possibly take a course on your phone. But I had a graduate student that year who told me that she did her coursework for me on her phone in her free time while she was at her night job. We were using Moodle and she just resized the web pages. I couldn't see how that worked but I knew an app would have made it better.

The second wave was adaption - using apps not specifically designed for education in courses. That was being done by individual teachers as they discovered and bought into the app world. Adaption requires some pedagogical changes. Mobile devices still were not acceptable (even banned) in some classrooms in 2011. It was the rare faculty member who said "Take out your phone..." and asked students to use it for class.

Now in this time of the pandemic, it is clear to schools, teachers, students, and parents how "educational" phones or tablets can be. Schools are supplying tablets the way we once supplied laptops. But even laptops are using apps. I'm sure app downloads are up in the past two months. App versions of Zoom and others have become common tools not only for educators but or personal use.

That move from personal to professional (business or education) use is critical to adoption or adaption/adaptation. As teachers started using their phones and apps more in their everyday screen time, the move to use them for teaching became easier.

Those 2011 audiences weren't sold on using apps in the first half of my presentation. They weren't using apps for themselves. Some did not have a smartphone. But they were hearing "There's an app for that" from friends, colleagues their students and on television commercials. They knew it was coming.

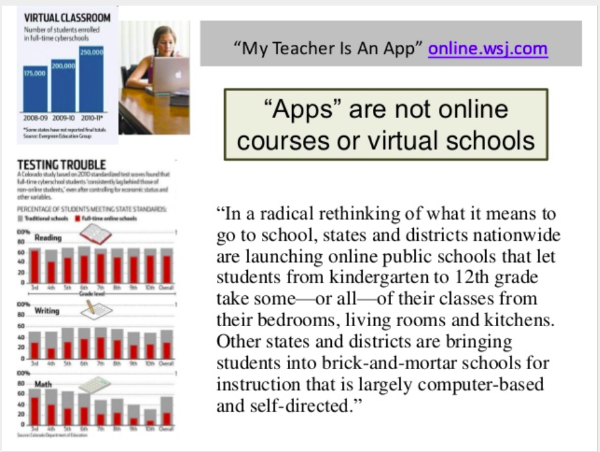

I caught their interest when I shifted to talking about why - even though I was an app evangelist - apps are NOT online courses or would virtual schools in the near future. (I find that educators generally like the status quo.) There was an article I pointed to that was headlined “My Teacher Is An App.” A provocative headline but the article did follow my point that things were changing but we wouldn't be there for quite a while.

The article said “In a radical rethinking of what it means to go to school, states and districts nationwide are launching online public schools that let students from kindergarten to 12th grade take some—or all—of their classes from their bedrooms, living rooms, and kitchens. Other states and districts are bringing students into brick-and-mortar schools for instruction that is largely computer-based and self-directed.”

That was not common in 2011 and still wasn't common in 2019 - but it is a lot closer to being true in the spring of 2020.

I wondered then if apps would be driving curriculum or would curriculum be driving app development. I'm pleased that the latter seems to be generally the case now.

I asked the audience if they believed that this reliance on smartphones and apps will "produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it because they will not practice their memory. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many Socrates on the things without instruction and written word, will, therefore, seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with since they are not wise but only appear wise.”

Those in the audience who did agree were right in line with Socrates in 340 BC since those were his words on his belief about the dangers of the written word. Socrates was wrong about the adoption of the written word into education.

My third wave was just beginning to form in 2011. That was colleges creating their own apps. I had a few examples of colleges adopting and adapting things like parking and events using commercial apps and GPS to navigate campuses or scheduling apps for campus calendars, courses, or facilities scheduling.

But do schools need to create their own apps or just purchase commercial ones that can be branded? I looked back to the development of school websites as an example. Initially, most schools bought a package or a vendor but along the way many schools took it on as an in-house operation, perhaps using some commercial products - a combination of creation and adaptation.

In 2011, may school websites weren't even dynamic enough ready for viewing on phones or tablets. But schools were creating their own apps and courses about how to develop apps were becoming a hot topic.

In 2020, there are plenty of no-code tools for app development (Airtable, Bubble, Zapier, Coda, Webflow) so that it doesn't take a wizard developer to make a fully functioning app.

If you are a teacher or student at any level K-20, the chances are excellent that you are using apps in your courses and on your campus.