Gogy: Peda, Andra and Situated Cognition

I was reading an article called "The Problem of 'Pedagogy' in a Web 2.0 Era" and it got me thinking about how often we throw around that term in higher education even though very few educators at that level have any formal training in it.

I was reading an article called "The Problem of 'Pedagogy' in a Web 2.0 Era" and it got me thinking about how often we throw around that term in higher education even though very few educators at that level have any formal training in it.Higher education faculty don't get any courses on pedagogy or learning theory in their degree programs. Faculty members in four-year universities are often researchers and their focus is on their research and not on how learning occurs and perhaps not even as much on their own disciplinary knowledge as those at other colleges.

Of course, there should be faculty development efforts at all colleges and those should include workshops and presentations to increase awareness of the basic research in learning theory of the past few decades as well as what is being found currently.

All teachers learn by teaching. That in itself is a learning theory that has several names attached to it. But that learning process is made more efficient by exposing faculty to what we know about pedagogy. That doesn't mean just learning the language of constructivism or Bloom's taxonomy. It means trying out lessons and being exposed to new approaches to what is often very old content.

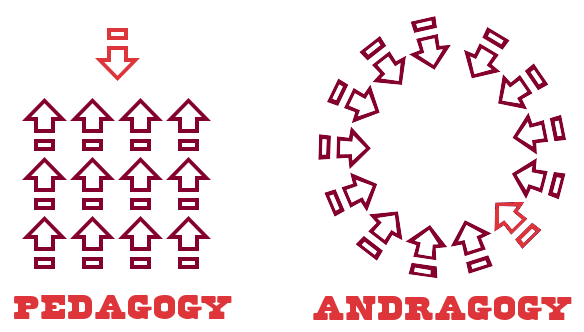

And if you are teaching older, non-traditional students, then you really should be aware of what has been found to work in the field of andragogy. Pedagogy literally means "leading children" and came first from studies of students in grades K-6 and then later included those in secondary school. Andragogy was a later area of study. Malcolm Knowles and others theorized that methods used to teach children are often not the most effective ways of teaching adults. I think many college professors would say that their students are often somewhere between those two -gogies. The 18 year old freshman, the 21 year old senior, and the 23 year old graduate student are very likely to sit in a classroom with a 28 year old freshman, 35 year old senior and a 50 year old graduate student.

I would love to be in a discussion with a group of interested educators about some learning theory like "situated cognition." If the topic is new to the participants, all the better. Situated cognition is the name given to the theory that knowing is inseparable from doing. It proposes that all knowledge is situated in activity which is bound to social, cultural and physical contexts.

To take this theory on means nothing less than making an epistemological shift from empiricism. To put it into action in a classroom would mean encouraging thinking on the fly rather than the typical back-and-forth of knowledge storage and retrieval. Cognition cannot be separated from the context.

If it sounds radical, it's because it is radical. And yet, students and teachers have been doing it throughout their lives - though probably not very often in a classroom setting.

Do I think this should be the new way to teach? No. But I would love to hear educators talking about it and about learning theories, pedagogy and andragogy with some of the same passion that they discuss their research, promotion and tenure, and contracts.

I was very pleased to see a post titled "Pedagogy – You Keep Using That Word… I Do Not Think It Means What You Think It Means" by Rolin Moe on his blog

I was very pleased to see a post titled "Pedagogy – You Keep Using That Word… I Do Not Think It Means What You Think It Means" by Rolin Moe on his blog  Though the brain at middle age isn't as sharp as it might have once been, it actually gets better at some things, like recognizing the central idea, the big picture.

Though the brain at middle age isn't as sharp as it might have once been, it actually gets better at some things, like recognizing the central idea, the big picture.  I'm not sure exactly what my reaction is to this report I read about on The Chronicle's

I'm not sure exactly what my reaction is to this report I read about on The Chronicle's