The Online Learning Perfect Storm

Awhile back, edX CEO Anant Agarwal wrote in Forbes "How Four Technologies Created The 'Perfect Storm' For Online Learning." The four technologies are cloud computing, video distribution at scale, gamification, and social networking. A commentary by Stephen Downes doesn't question the impact these four have had on online learning, but he does question Agarwal's claim that each is a part of edX.

Awhile back, edX CEO Anant Agarwal wrote in Forbes "How Four Technologies Created The 'Perfect Storm' For Online Learning." The four technologies are cloud computing, video distribution at scale, gamification, and social networking. A commentary by Stephen Downes doesn't question the impact these four have had on online learning, but he does question Agarwal's claim that each is a part of edX.

For example, he notes that the claim that "social networking" is present is because it uses a discussion board. That is certainly a stretch. For gamification he cites "simulation-based games, virtual labs, and other interactive assignments," none of which is integral to edX.

Downes considers the article "lightweight" but though there may not be a perfect storm it is worth noting the impact of those four things beyond edX.

Cloud computing has allowed exponential scalability in many sectors including online learning. Online learning platforms (Does anyone say learning management systems anymore?) became more responsive and faster.

Scalability was certainly key to the emergence of MOOCs. When some colleges tried their own MOOC offerings they realized that they couldn't handle the jump from courses with 25 or 100 students to ones with thousands of students. Of curse, even if you are still offering smaller online courses, the cloud allows all students to benefit from faster, more responsive platforms.

Video has been a part of online learning for 40 years if you go back to ITV, videotapes, CDs and DVDs. Broadbandallowed video to stream and sharing and distribution really hit about the same time as MOOCs were starting to gain initial momentum. YouTube and Vimeo allowed some smaller institutions a way to distribute high-quality videos.

When I was at NJIT, I got the university to sign on in 2007 as one of the first of 16 universities to use Apple's iTunes U. That gave us a much larger presence in online learning. I wrote about it extensively on this blog. But iTunes U didn't grab the market share the way MOOCs and YouTube did. The interface was not friendly to universities or to users. You don't hear it mentioned much by educators now and I doubt that it will exist in 2020.

iTunes U was important for sharing university lectures and some supporting documents. It was more open than what we would expect from Apple because the content was opened up by the institutions (colleges and also educational institutions like museums). I consider it an early tool in the MOOC movement.

Gamification has been a buzzword for a long time, but it still hasn't made its way into most learning platforms by for-profits or in colleges. There's no doubt that instant feedback and more active engagement in the learning process produces better success, but I find faculty still back off at the word gamification. Some of that fear or disdain is because they associate it with videogames and gaming sounds less "educational." This is a misconception, but one that has persisted. I always used to say that just say "simulation" instead of gamification and you'll get more buy-in from faculty. Sometimes that worked.

Simulations that use game strategies and components can be used in virtual labs and many interactive activities, knowledge checks (graded or not) and assignments in order to promote higher-order thinking tasks such as design, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The "fun factor" shouldn't be ignored although that is part of the hesitation from faculty. There is this sadly persistent idea that learning is supposed to be difficult and not fun.

Social networking came on strong in the era of Web 2.0. Today it comes in for a lot of criticism. I believe that many educators who were using Twitter, Facebook and other social sites in their teaching have backed away. part of that is the criticism and privacy issues on such sites and part of it is that there are some tools built into platforms that allow for a more private social experience. However, posting your thoughts in an LMS for the rest of the class really doesn't duplicate or approach the experience of posting it online for a large part of the world. Twitter boasts 330 million monthly active users (as of 2019 Q1) and 40 percent (134 million) use the service on a daily basis (Twitter, 2019). The chance to interact and possibly collaborate across the globe is no small thing.

What will create the next perfect storm in online learning? Agarwal suggests that the next four high-impact technologies will be AI, big data analytics, AR/VR and robotics.

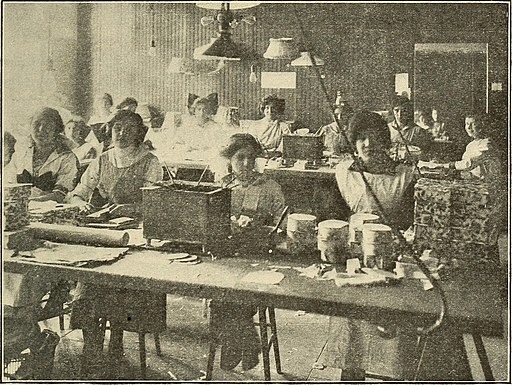

This post follows the previous one about vocational education in the U.S. There appears to be a resurgence of the "alternative to college" option in the 21st century.

This post follows the previous one about vocational education in the U.S. There appears to be a resurgence of the "alternative to college" option in the 21st century.