Reading on Screens Revisited

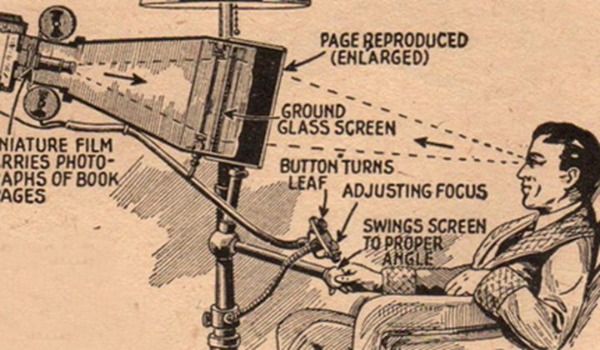

I recently came across an article in Smithsonian magazine that was rather deceptively titled "The iPad of 1935." The illustration above comes from that article and originally appeared in the April 1935 issue of Everyday Science and Mechanics magazine. At that time they were thinking that since it is possible to photograph books and also project them on a screen for examination, that perhaps this would be the way we would read. Their illustration is probably closer to watching a PowerPoint presentation than an iPad, but the idea of putting books on a screen is not just an idea of the 21st century.

That article made me do a search on this blog to see what I have written about ebooks. In 2012, I wrote about digital textbooks ("Can Schools Adopt Digital Textbooks By 2017?") I should have revisited that article in 2017 to see what had come to pass. In 2020, I can say that publishers, schools and students have adopted ebooks and digital textbooks, but there are still plenty of books on paper being used by students.

That 1935 contraption uses a roll of miniature film with pages as the "book." It reminds me of the microfilm readers I used as an undergraduate in the library. As the article notes: "microfilm had been patented in 1895 and first practically used in 1925; the New York Times began copying its every edition onto microfilm in 1935."

It took about 70 more years for handheld digital readers that we use to come on the scene and the transition is still taking place.

Though I have an iPad and a Kindle, my home and office are still filled with paper books and magazines. I would say that the bulk of my daily reading is done on a screen but the screen is on my phone and laptop. When I have taught college classes online or on-site, I have offered texts as ebooks when possible as an option. I still find that some students prefer a Gutenberg-style book on paper.

That 2012 post of mine referenced an article about the then Education Secretary Arne Duncan and Federal Communications Commission chairman Julius Genachowski issuing a challenge to schools and publishers to get digital textbooks to students by 2017.

In 2012, there was a "Digital Learning Day" where there were discussions on transitioning K-12 schools to digital learning and using technology to transform how teachers teach and students learn inside and outside of the classroom. They issued "The Digital Textbook Playbook" guide which went far beyond textbooks and included information about determining broadband infrastructure for schools and classrooms, leveraging home and community broadband to extend the digital learning environment and understanding necessary device considerations along with some "lessons learned" from school districts that had engaged in successful transitions to digital learning. The 2012 playbook can be downloaded and it's interesting to see what has changed in the 8 years since it was written. Those changes would include a new administration with different objectives from the Obama era.

The playbook defines a "true digital textbook" as "an interactive set of learning content and tools accessed via a laptop, tablet, or other advanced device." Being that this effort was on K-12, the perspectives of key users was students, teachers, and parents.

Looking ahead and making predictions is a December and January tradition. I feel like most of the time those predictions don't come true, but we often don't look back to check them. In education and especially in technology, it's hard to predict what is coming in the year ahead. That is why I had to look at an article I saw that was titled "

Looking ahead and making predictions is a December and January tradition. I feel like most of the time those predictions don't come true, but we often don't look back to check them. In education and especially in technology, it's hard to predict what is coming in the year ahead. That is why I had to look at an article I saw that was titled "

Social listening (or social media monitoring) is paying attention to your brand's social media channels for:

Social listening (or social media monitoring) is paying attention to your brand's social media channels for: