The MOOC of One

I'll have more to say on the future of the form, but in brief, I feel that it will have less traction in academia with formal, credit courses and greater traction with non-credit programs, lifelong learning and professional development.

The slides below seem to be moving in the same direction of thinking. In this talk, Stephen Downes looks at the transition of the massive open online course to applications in the personal learning environment.

He says that "I question what it is to become 'one' - whether it be one course graduate, one citizen of the community, or one educated person. I argue that (say) 'being a doctor' isn't about having remembered the right content, not about having done the right things, not even about having the right feelings, nor about having the right mental representations - being one is about growing and developing a certain way."

He offers audio at http://www.downes.ca/presentation/336

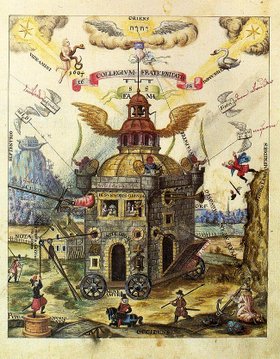

The Invisible College (whose emblematic image is shown here in an illustration from Speculum sophicum Rhodo-stauroticum, a 1618 work by Theophilus Schweighardt) was the Rosicrucian College, identified by Frances Yates as the "Invisible College of the Rosy Cross".

The Invisible College (whose emblematic image is shown here in an illustration from Speculum sophicum Rhodo-stauroticum, a 1618 work by Theophilus Schweighardt) was the Rosicrucian College, identified by Frances Yates as the "Invisible College of the Rosy Cross".

The concept and the term was applied to a global network of scientists by Caroline S. Wagner in her book,

The concept and the term was applied to a global network of scientists by Caroline S. Wagner in her book,  . It has found its way into fiction like

. It has found its way into fiction like  by Dan Brown and

by Dan Brown and  by Umberto Eco.

by Umberto Eco. (such as

(such as  ).

).